CollectionBuilder CSV

Digital Collection Magic with Static Web Technologies

John Milton

The poet and polemicist John Milton was perhaps the most influential English literary forebear for Hunt. Although from childhood Hunt steeped himself in the works of the canonical giants Chaucer, Spenser, and Shakespeare, Milton was for him something of an idol (Roe 22). Of the twenty-one public figures included in Hunt’s Hair Book, Milton is the only one whose page features a sonnet Hunt penned in response to it. Hunt wrote three sonnets about this lock of Milton’s hair, and after showing it to his friend John Keats, Keats also wrote a tributary poem. While the lock might be dismissed as a mere curio, and as a potentially spurious one at that, Hunt’s sonnets in response to his encounter with Milton’s hair are remarkable for Hunt’s emphasis of Milton’s presence over his absence. While Wordsworth’s “London, 1802” uses the sonnet form to apostrophize Milton, Hunt’s sonnets treat Milton’s hair as offering the synecdochic presence of the author. Hence, while Wordsworth’s Milton is a remote and sublime figure, Hunt figures Milton as a sociable and accessible influence.

The period in which Hunt was tried for seditious libel and then served a two-year sentence in Surrey Gaol, from late 1812 to early 1815, showcases both Milton’s literary influence and Hunt’s idolization of Milton. During Hunt’s trial for seditious libel, he associated himself with Milton in an act of resistance to what he took to be a wholly unjust proceeding: “Hunt was clutching a copy of Milton’s masque, Comus, as a talisman of invincible virtue” (Roe 176). The hero of Comus, the Lady, successfully fends off temptation until, when she is forcibly compromised, her virtue elicits the extraordinary assistance of the goddess Sabrina. Though Hunt himself received no miraculous rescue and was sentenced to two years in prison, he seems to have continued to reflect on Comus during his prison term. Milton’s influence can be felt in the masque Hunt wrote during this period, The Descent of Liberty, whose preface provides a critical survey of the masque genre, including Milton’s Comus. Another of Hunt’s works written during his imprisonment, The Story of the Rimini, also alludes heavily to Milton’s poetry but this time to Paradise Lost (Roe 249). Hunt claims to have habitually read Milton which in Surrey Gaol (Roe 186). His elaborately decorated his cell, “with books, flowery wallpaper, and a bust of Milton,” also reflected Hunt’s idolization of Milton (Tomko 286). Hunt’s persistent financial problems stemmed in part from extravagant spending habits, exemplified by a splurge of £50 on a portrait of Milton (Roe 167). Hunt brought this portrait to Surrey Gaol with him, where the “portrait of Milton hung on one wall” (Holden 76). Hunt’s possession of these artworks depicting Milton suggests an attachment not only to Milton’s writing but also to Milton the man as an accessible and comforting presence.

As Hunt matured into middle age, he developed a preference for Milton’s early poetry over his late works. This preference seems to stem from a rejection of “the offensive Christianity of Milton’s epics and thus Hunt returns to the early poems that are unhurt by this terrifying theology” (Wittreich 19). In Imagination and Fancy, Hunt states this preference for Milton’s early poetry over his late masterpieces:

Hunt explicitly links the distasteful pride he detects in Milton’s later works to Milton’s experience of total vision loss, and Milton’s plaintive descriptions of his blindness in Paradise Lost perhaps encourage the view of the blind Milton as a solitary figure. But such self-representation is, of course, complicated by its status within a work of fiction, and early biographies of Milton paint a different picture–one in which Milton was fairly social, surrounded by friends and family who read to him and served as his amanuenses.

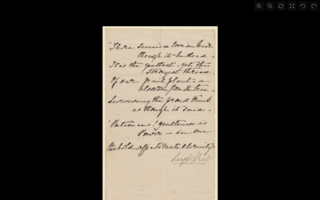

The material relic from Milton’s body–Hunt’s lock of his hair–served as a conduit through which Hunt could access the sociable Milton. It was this lock that Hunt first acquired, and it was the jewel of his collection. While some scholars have speculated that Hunt’s lock of Milton’s hair was “taken away from Milton’s gravesite,” perhaps when Milton’s coffin was exhumed in 1790, both Hunt’s explanation of the lock’s provenance and the fact that the lock of Milton’s hair in Hunt’s book is dark auburn, rather than gray, suggest otherwise (Semenza 165). Hunt wrote three sonnets on Milton’s lock of hair, all of which were first published in Foliage. In the most famous of these sonnets, Hunt imbues Milton’s hair with an animacy activated by Hunt’s own breath. Hunt also depicts “Milton as a partaker in his conversation… which differs from the Romantic apprehension of the bard as an isolated, prophetic figure” (Stabler 103). Indeed, “for Hunt, Milton’s hair is a medium through which the great poet might still maintain a bodily presence, albeit a fractured one” (Hess 214). Hence, Hunt regards Milton as an accessible presence, defying “traditional Romantic emphases on isolated sublimity” (Tomko 288). Long after Hunt showed Keats Milton’s hair, Hunt chose to share some of this lock with the Victorian poet Robert Browning, who placed it in a locket alongside the hair of his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning. The locket is held by the Keats-Shelley Memorial House in Rome.

Keats’s “Lines on Seeing a Lock of Milton’s Hair”:

Hunt’s three sonnets on the subject: